Rats and Astronauts: Street Art in Oaxaca

Listen below. Click “globe” for more languages.

Famed for its artistic traditions in weaving, pottery and painted wooden animal carvings known as alebrijes, the Mexican city of Oaxaca is also brimming with contemporary art. Museums and galleries dot the central area, particularly north of the Zocalo, the central plaza, but Oaxaca also has a thriving street art scene.

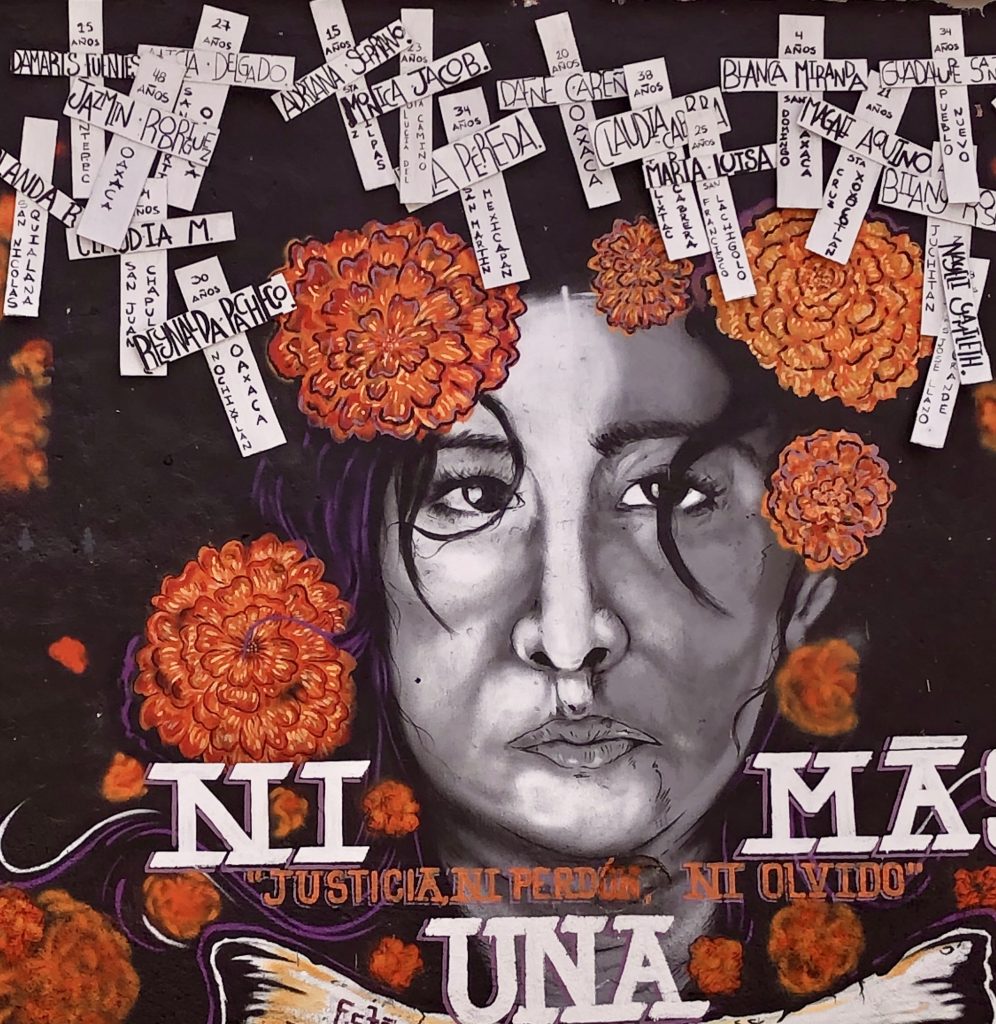

On a recent trip, my family and I explored by bicycle the bounty of artwork painted, stenciled, pasted and sprayed onto the city’s walls. We booked a half-day tour with Coyote Aventuras, and our guide Diana Shai led us through the city’s narrow, crowded streets, on a four-hour exploration of the city’s street art. The varied artwork generally fell into three categories: woodcut posters with political images, day of the dead murals, and artists’ large signature pieces.

Indigenous Political Protest in Oaxaca

Oaxaca, which sits in the foothills of the Sierra Madres in Southeastern Mexico, was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and is known for its Colonial architecture and strong indigenous roots. The Zapotec and Mixtec, who lived in the area for thousands of years before the first Spanish arrived in 1521, continue to exert a significant influence culturally.

On a recent warm Monday morning, we met our guide Shai and collected our rented bicycles near the Plaza Santa Domingo, a hub of woodblock and printmaking activity. We stopped first to examine a group of political posters wheat pasted onto a nondescript wall, many signed by The Revolutionary Union of Art Workers (URTARTE), one of the many art collectives in the city that makes eye-catching political art.

Journalists at Risk

The first poster depicted one of Mexico’s first female journalists, Leona Vicario, who fought for independence and was heralded as “mother” of the country. The black and white image is comprised of detailed woodcuts using intricate shading to produce a striking image of an upright woman, holding a puppet meant to represent a priest. Beneath Vicario, a bent-over politician licks the words spilling from her typewriter. Though Vicario died in 1842, she’s addressing a more modern problem in this depiction, as is evidenced by the words “pedophilia,” spiraling out from her typewriter.

Further down the wall was another woodcut poster, similar in style, commemorating a modern journalist, Maria del Sol Cruz Jarquín, an Oaxacan who was killed last June while covering an election campaign. “Mexico is a dangerous place to be a journalist,” explained Shai.

The Committee to Protect Journalists backs up those allegations with facts. “Mexico is the deadliest country for journalists in the Western hemisphere,” according to CPJ research. In 2018, “at least four were murdered in the country in direct retaliation for their work.”

Commemorating Murdered Protestors

The next poster we examined, also on the same wall, was of a young woman holding an enormous heart with the number 43 at the top. Made in a similar style as the others, a detailed black-and-white woodcut, Shai told us the number represents the 2014 disappearance (and presumed death) of 43 students in the southern state of Guerrero who were headed to a demonstration commemorating a 1968 massacre of protestors. An official investigation claimed the local police gave the students to a drug cartel, who in turn, killed them. Most people do not believe this explanation and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who assumed office in 2018, has ordered a new investigation.

Another striking poster, dense with symbolism of corruption by politicians and the church, caught my eye. “Without corn, there is no country,” was the translation of one phrase embedded in the intertwined skulls and devils. Shai told us the poster is addressing the passage of NAFTA, which harmed corn production in Mexico. Farmers could not compete with U.S. prices and many local, small farms went out of business as Mexico began importing substantial amounts of corn from the U.S. At the center of the poster was a rat, symbolizing the (former) president and a dinosaur, indicating the “old” regime.

“Graphic arts are a weapon to tell people about the real version of the news,” Shai said. And indeed, with her help, we learned a tremendous amount about the politics and violence of the area and the local resistance to corruption organized by artists.

Day of the Dead

After Shai’s detailed explanations about the symbolism and the meaning of the posters around Plaza Santa Domingo, we bicycled five minutes Northeast to the Barrio de Jalatlaco, a quiet, historic neighborhood, to look at a different type of street art. Shai told us the neighborhood had strong traditions around Day of the Dead, which was evident from the many murals painted on businesses and houses.

Day of the Dead, or Día de los Muertos, is a Mexican holiday honoring memories of the departed, who are believed to awake and celebrate with the living on November first and second.

The Temple de San Matias Jalatlaco, a 17th-century church, anchors the neighborhood and the plaza serves as a gathering spot for the festivities. Across the cobblestone street is one of the most striking murals in the neighborhood, spread across two walls of the corner building. Skeletons are drinking, chatting with each other, and one athletically inclined skeleton does a split near the roof.

Around the neighborhood, other houses hosted ‘Calavera’ murals joyfully depicting skeletons engaged in all kinds of activities— listening to an MP3 player, climbing a tree, and pulling carts to name a few. Some referenced the household altars people create every year on Day of the Dead for their deceased family members, which usually include flowers and food.

One of my favorites depicted several women skeletons with long black braids, cheerfully drinking with their arms slung around each other. Shai told us that it commemorated a special parade for women that takes place nearby during Day of the Dead.

Other Murals in Oaxaca

With Shai in the lead, we quickly found our way to a mural commemorating María Sabina, a traditional healer, who used psychedelic mushrooms in her ceremonies. Sabina originally opened her ceremonies to Westerners, including allegedly celebrities like the Beatles and Bob Dylan, but the involvement of Westerners ultimately corrupted the traditional ceremonies.

Sabina, painted with a black dog above her head, believed plants had personalities and expressed emotions, Shai explained as she pointed to the plants depicted to her left that are meant to express seriousness, anger, and creativity in the heads that top their abstract bodies.

Tucked in an alleyway nearby we discovered another large mural, notable for the image of a spaceman floating above the desert as he pulls his heart from a square hole in his spacesuit. A statement about technology and nature, the graffiti-style mural speaks loudly with brilliant colors and larger than life, juxtaposing imagery.

When we asked Shai about the greater meaning or symbolism for the spaceman, she shrugged. Artists paint what inspires them and that can range from specific political messages to broader themes or commemorations that are more personal to them. With Shai’s help, we were able to decode and contextualize Oaxaca’s street art, which enriched our understanding of the city and the experiences of its people.

Book Your Stay in Oaxaca, Mexico

Use the interactive map below to search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo, and more. You can move the map to search for accommodations in other areas and also use the filter to find restaurants, purchase tickets for tours and attractions, and locate interesting points of interest!

Eliza Amon has worked as a journalist for nearly 20 years with articles published in The New York Times, Harper’s Magazine and Bloomberg News among others. Eliza is the Editor for World Footprints and currently lives in Seattle where she is thrilled to have the opportunity to discover new adventures in the Pacific Northwest.