The Rise and Fall of Goldsboro, Florida: An African American Town

goldsboro art square

Posted February 7, 2024

Many people know the story of the African American town Rosewood from the movie about the massacre, but how many of us have heard of Goldsboro, Florida, the second black incorporated city in the United States, which also thrived and was subsequently destroyed? Boasting famous residents, like the writer Zora Neal Hurston, the city’s history has been preserved through the creation of the Goldsboro Cultural Arts District, with a museum as it’s the centerpiece.

I learned about Goldsboro on a recent press visit to Sanford, Florida. Pasha Baker, the CEO of Goldsboro Westside Community Historical Association, met with us and told us about the city while we had lunch at Tennessee Truffle, a local restaurant. I was intrigued and, along with several others on my tour, visited the museum and the other places that tell Goldsboro’s history, accompanied by Pasha.

Goldsboro’s Founding

Goldsboro was founded in 1891 by William Clark. He was the brother of Joseph Clark, who several years earlier started Eatonville, Florida’s first black town in neighboring Orange County. Goldsboro was composed mainly of laborers, railroad workers, former slaves, and itinerate farm workers who helped produce celery, Sanford’s most famous crop. It was a peaceful community until 1911. That year, on April 26, a Florida State Representative and former Sanford mayor named Forrest Lake, pushed through a bill in Tallahassee that dissolved Goldsboro’s charter and forcibly annexed it into Sanford.

Pasha explained the motivation. “It was the land, of course. Without Goldsboro, Sanford was just that small place next to Lake Monroe.” Representative Lake believed Goldsboro and the neighboring town of Sanford Heights blocked the city’s plans for expansion, so he destroyed Goldsboro in order to make Sanford more prosperous. The townspeople of Goldsboro spent the following forty years suing to restore the town’s charter but were not successful.

Goldsboro was gone as a town but not forgotten. It lived on in the memory of the Goldsboro residents. In 2009, Francis Oliver, a second generation Goldsboro resident, began a movement. She used her small teacher’s pension to help spark the Goldsboro West Side Community Historical Association. Their purpose was to preserve the memory of Goldsboro. For over 40 years, Oliver collected the town’s history through various artifacts, including pictures and documents. In 2011, on the 100th anniversary of Goldsboro’s demise, The Goldsboro Museum opened.

The Goldsboro Museum

Pasha ushered us into the museum, housed in a modest doublewide trailer, where we met Francis Oliver, Association founder and curator of the museum. History blossomed all around us. Handmade quilts from the late 19th and early 20th century were among the first artifacts we saw. A room labeled the “Trailblazers of Goldsboro” showed photos of early Goldsboro citizens. Another room showed the symbols and items used to degrade black people like pickaninny and mammy dolls. There were also maps and historical books related to Goldsboro.

The museum had items from everyday life in Goldsboro, including a barber chair from Mr. Jim Green’s OK Barber Shop, which opened in 1923. Also on display were an old hand water pump from before the days of elective powered well pumps, an antique cash register, and children’s toys and games from the early 20th century

Many musicians came to Goldsboro during the segregation era and the museum commemorates those visits. The African American sports heroes who visited or grew up in Goldsboro are also represented, including Jackie Robinson, who was scheduled to play his first game in Sanford. The Ku Klux Klan forced the city to prevent Robinson from playing, so he stayed in a Goldsboro resident’s house that night. The house is now known as The Jackie Robinson House, though he never returned to Sanford.

Goldsboro‘s most famous resident, Zora Neale Hurston, lived in the community for two short periods and the museum has a newspaper story displayed about her life there. In 1912, Hurston stayed at her brother’s house. She lived in the city again in 1933, this time at a local boarding house while writing Jonah’s Gourd Vine. She lived there for several months and was evicted on the same day a publisher accepted the book.

Crooms Academy

After the museum opened, the Goldsboro Cultural Arts District was founded to create additional sites with important historical ties to the community. We visited Crooms Academy Museum, which was Seminole County’s first high school for African-American students and was founded in 1926 by Professor Joseph N. Crooms. It continued as an all-black school until 1970 when statewide desegregation began. It still exists as a public magnet school.

The simple frame cottage that houses the Crooms Academy memorabilia, next door to the Goldsboro Museum, is filled with memorabilia like yearbooks and pictures depicting Goldsboro student life in the 1920s.

Francis Oliver Cultural Arts Center

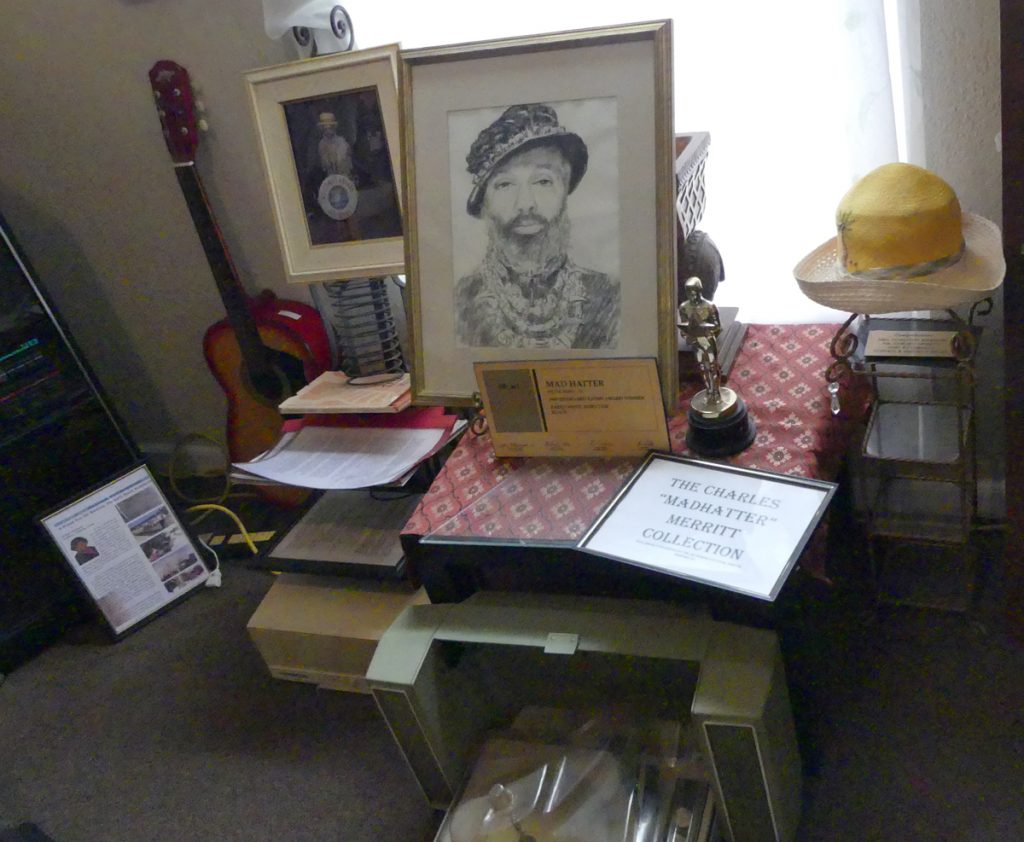

The Francis Oliver Cultural Arts Center across the street from the museum is filled with exhibits of all kinds of arts. There are paintings, musical instruments, posters, photos, and more, all artfully arranged with information about their subject’s relationship to Goldsboro. One exhibit focuses on Charles “Mad Hatter” Merritt. Merritt was a Goldsboro native who became a legendary disk jockey in Mobile known for playing rhythm and blues.

You’ll also find photographs of Civil Rights figures and marches. Some of the paintings housed in the center include portraits of contemporary African-Americans, including Prince, Michelle Obama, and Francis Oliver.

Outdoor Sites

Outside the museum, we visited the Goldsboro Heritage & Art Garden. The community grows organic produce and offers it free to residents. The historical society also receives some income from the sale of the produce to local restaurants, like the one we lunched in, the Tennessee Truffle in Sanford.

The Goldsboro Arts Square is another green space, filled with folk art by local artists such as Jeff Sonksen and members of The Crealdé School of Art. Among the unusual art, is a stone tribute to B. B. King and large fence paintings of Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King.

The African American Cemetery

Page Jackson Cemetery, another historical site, is named for Page Jackson, a local white landowner who donated land to the African American community around 1830, so members of the black community could be respectfully buried. It is the final resting place for early former slaves, residents before and after Goldsboro‘s incorporation and veterans of the Civil War, World War I and World War II. The cemetery is overgrown but is slowly being reclaimed by volunteer workers.

Drew Bundini Brown is among those buried there. Brown’s name might not be immediately recognizable, but his words are. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” was his brainchild. Brown was the corner man for Muhammad Ali and wrote many of the taunts Ali threw out at his opponents. Zora Neal Hurston’s family plot is there although she is buried in Fort Pierce.

These historic sites tell Goldsboro’s story and allow its history to live on though the city is officially gone.

Book Your Stay in Goldsboro, Florida

Search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo, and more. You can move the map to search for accommodations in other areas and also use the filter to find restaurants, purchase tickets for tours and attractions, and locate interesting points of interest!

Join the community!

Join our community to receive special updates (we keep your private info locked.)