Finding the Common Thread at the Pinkas Synagogue, Prague

Pinkas Synagogue

By Nicole Banks

Posted March 3, 2021

The Holocaust is arguably the most horrific genocide in modern history. Between 1933 and 1945, around six million European Jews and millions of others were murdered by the German Nazi regime. At least a million of those killed were children. I knew this before I visited Prague, but I can’t honestly say that I turned my mind to it that often. These were events that happened on the opposite side of the world to where I live, long before I was born, to people wholly unconnected with me. I wasn’t even aware of having met a Jewish person before.

Standing in front of a memorial to the 77,297 Czech Jews who were massacred during the Holocaust, however, it’s not quite so easy for me to dismiss. I’m at the Pinkas Synagogue, one of six Jewish monuments which make up the Prague Jewish Museum.

At first glance, the Pinkas Synagogue is an understated-looking building. The beige exterior and terracotta-coloured roof tiles don’t shout age to me. Only the windows give my untrained eye any indication of it having been constructed almost 500 years earlier. The multi-paned arches set within square faded brown frames lend a dark and sombre tone to what would otherwise seem sunny. As they approach the entrance, the men are handed navy-blue paper yarmulkes (skull caps) to wear inside the synagogue as a sign of respect.

From the archway inside, all I can see are large sections of a cream-coloured wall covered in what looks like black and red static. Other tourists stand close to the walls, peering at them and chatting softly to their companions. A few steps in and I can see what’s caught their attention, as the blur of black and red converges into rows of names and dates.

Tens of thousands of murdered men, women and children are remembered on these walls, painstakingly listed by hand in neat capitals. I can sense the respect of those undertaking the task, their small neat handwriting indicating slow deliberate strokes. I can still see what looks like pencil marks, lines drawn prior to writing I assume to ensure the rows remained straight.

Hearing the number 77,297 has nowhere near the effect of seeing each of those 77,297 people identified by name, along with the date they were born and the date they died (or more often were last known to be alive). Listed out like that, the human cost seems much greater. In most cases, whole families seem to have been wiped out. A blood-red surname in capitals is often followed by a succession of given names, each divided by a tiny yellow star. The names keep coming, and I continue to follow them around that room and into the next one, where two young women stand contemplating the large arched wall at the end of the room, while a middle-aged woman (who I assume is a staff member) sits to one side on a chair listlessly scrolling through her phone.

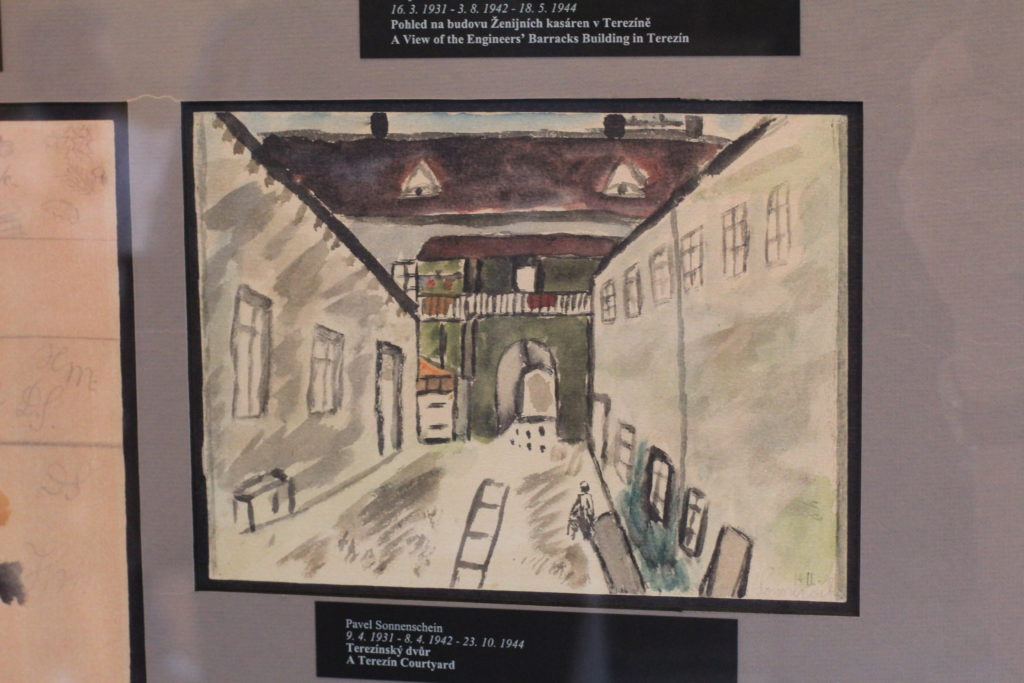

Eventually the names cease, as I enter another room which is narrower and more dimly lit than the rooms preceding it. Glass cabinets line the walls, full of children’s paintings and drawings. I’m at a loss initially as to why these are here, until I see a plaque about an artist called Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. These paintings and drawings are the result of lessons Dicker-Brandeis conducted with the children in the Terezin ghetto prior to her deportation to Auschwitz in October 1944. Most of these children ultimately suffered the same fate.

Any child today could have drawn these images, imbued them with their dreams and memories. A couple of the drawings are accompanied by photographs of the children who drew them. I had struggled enough with the drawings and the names, seeing their faces is a whole other level of gut-wrenching.

One of the photographs is of a young girl, a gentle smile on her lips as she holds a ball in one small, chubby hand. The plaque beneath identifies her as Gertruda Eisinger and follows with the dates: 27.12.1931 – 16.7.1942 – 23.10.1944. The first date is her date of birth, the last her date of death (or when she was last known to be alive). I can’t find any explanation for the middle date; I assume it’s when the photograph was taken. She was 12 years old when she was killed. A coloured pencil drawing of what looks like children bobsledding in the snow is beneath the plaque, signed with her name in clear cursive.

There are two other photographs to the right of Gertruda’s. The first is of two young brothers, one with his arms lovingly wrapped around the other, both smiling. The boys are Robert and Kamil Sattler. The other photograph is of Robert and Kamil with their parents and brother Karel, all dressed neatly in caps and overcoats, seemingly part of a crowd going about their day. Plaques above confirm Karel and Robert were 11 and 10 years old respectively when they were killed. Karel’s drawing is of a funeral. Robert has drawn a train.

I find myself moving between the photographs, trying to reconcile what happened to these smiling children. A final glance at Gertruda’s innocent expression is enough to overcome the restraint that has become increasingly difficult to maintain. I begin to weep uncontrollably and have to leave the room, secreting myself in a corner. I sob, embarrassed but unable to stop the outpour, as my boyfriend holds me.

After about a minute he ushers me outside, but it’s not much better out here. The external wall has its own collection of photographs: families clustered together between Nazi soldiers preparing to be sent to the ghetto, women and children packed up and sent to Auschwitz, women stripped naked and murdered by Nazis. The photographs are complemented by a summary of the many horrific ways in which Czech Jews were killed.

I eventually escape the synagogue via the Old Jewish Cemetery, a centuries-old jumble of overlapping, toppling headstones that has the appearance of a mouth with too many teeth, the roots of which run ten graves deep in places.

It’s quiet this afternoon at what I understand is usually a busy attraction. I’m grateful for the opportunity to calm and steady my thoughts as I weave through the crooked stones, peering at some of the symbols to try and guess who their occupants were in life. I imagine some of the people memorialised inside the synagogue, which I can still see looming in the distance, once walked among these graves like I am.

Travel has influenced my view of the world, teaching me to appreciate the differences and notice the similarities between another culture and my own. What once seemed distant from my own experience – long ago, far away, other – starts to bear significance as I realise that irrespective of when, where or who is affected, we are all linked by the common thread of our humanity.

Cover: “Pinkas Synagogue Pinkasova synagoga” by Paul and Jill is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Book Your Stay Now in Pinkas Synagogue, Prague

Use the interactive map below to search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo, and more. You can move the map to search for accommodations in other areas and also use the filter to find restaurants, purchase tickets for tours and attractions, and locate interesting points of interest!