Arcosanti: An Experiment in the Arizona Desert

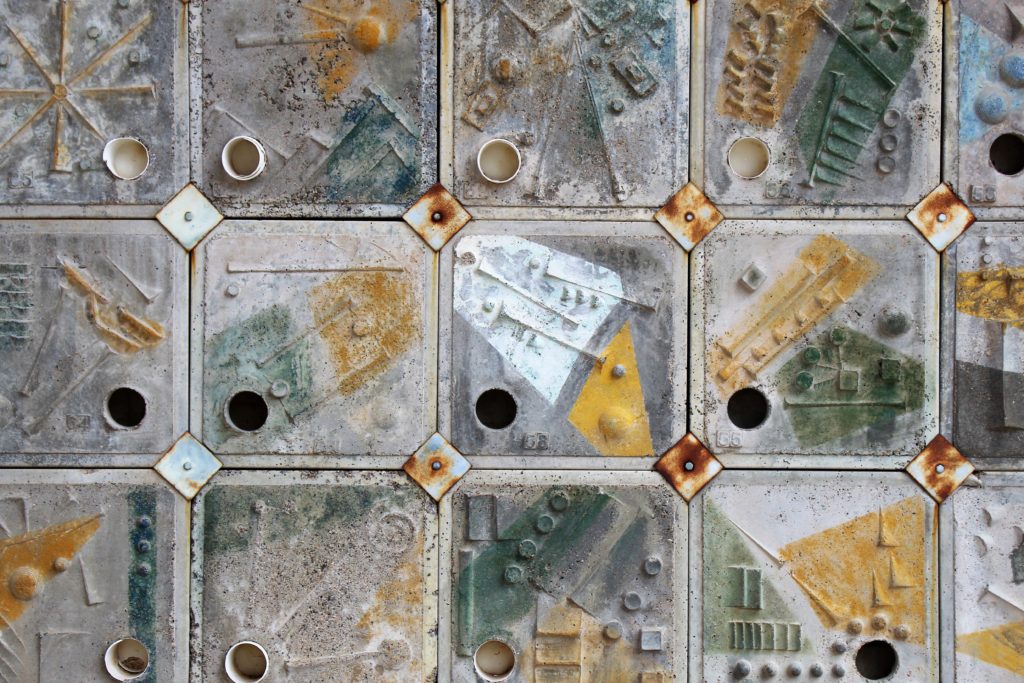

Arcosanti silt casting workshop scaled

Posted April 4, 2025

A Prototype of Arcology

It is peaceful in the wilderness outside Mayer, Arizona. I draw back the curtain that covers the glass wall of our room in Arcosanti’s guesthouse. Sunlight pours over the gray concrete floor and walls, highlighting a ceiling painted with flowers in the style of artist Paolo Soleri. I stand at the glass wall, drinking in the stark beauty of the small valley below us and the mesa beyond.

Out of view, built into the hill above, rises Arcosanti, a prototype of arcology. Arcology, a concept coined by Soleri himself by combining “architecture” and “ecology,” is the idea that architecture can be in harmony with the landscape. With its midcentury modern circular windows, concrete arches, and myriad of rooms built right into the hillside, Arcosanti is exactly that. Even the trendy 1970s color scheme—mustard, red-orange, and sage—complement the picturesque Southwestern scenery.

Although it’s not entirely independent of the outside world, Arcosanti was intended to be as off-grid as possible and boasts several successful experiments in sustainability, including on-site water treatment. Best of all, Arcosanti’s structures use passive heating and cooling, which harness natural sun and wind patterns to keep living spaces comfortable all year round.

Working at Arcosanti

At 9:00 AM sharp, the high-desert quietude is broken by the sound of 1970s rock music blaring over the landscape. My husband wrangles our squirmy two-year-old as we follow the sound of the music to a hillside half-dome structure that serves as the metal casting workshop for Arcosanti—and the source of the music.

Under the dome, a dozen or so residents of Arcosanti go about their jobs in gloves and protective goggles. Despite the banging of concrete and metal, all we can hear is Bob Segar’s voice: “If I ever get outta here, I’m going to Katmandu…” The workers are all smiles and energy, buzzing around the many tasks like a well-oiled machine. Someone mouths the words to the music, two complete a task together and share an enthusiastic high-ten.

Then, as if someone clapped a hand over Segar’s mouth, the workshop goes silent. The workers become still and smiles turn to expressions of intense focus. Even my toddler notices the change and stops wiggling for a moment. It’s time for the bronze pour.

We watch as two men each grasp the end of a pole that holds a huge bucket of red-hot liquid metal. In silence, they pour the glowing molten bronze into bell molds, keeping in step with one another and listening carefully for any warning of risk as the dangerous task is performed.

Once each mold has been filled, the two men return their empty bucket to be refilled and give the signal that their task is complete. A cheer explodes in the workshop. “Good job, guys!” my toddler shouts. The music is cranked up again, and we mount the stairs that lead us up the hill, past the round windows of homes set into the hillside, along a rainbow-painted amphitheater, and into the midcentury-modern shop towers over the hill and dusty valley below.

It’s not hard to see that Paolo Soleri and his disciples sought not only to build with the landscape, but also with relationships in mind. Everyone here has a job to do, whether that means cultivating olives, keeping the grounds, or creating the wind bells that financially support the community. Arcosanti is designed vertically to save space, and created to be dense, urban and walkable.

Really, it’s the exact opposite of the urban sprawl of metropolitan Phoenix that lies 70 miles south of Arcosanti. As a native Phoenician, I can understand why Soleri sought to escape the fast-spreading city, where most working residents hardly know their neighbors and commute alone for 45 minutes each direction, only to return to homes surrounded by 6-foot block walls. There’s certainly an appeal to living and working in a community, and the comradery I see in the residents of Arcosanti is refreshing.

Visiting Arcosanti

To preserve the privacy of Arcosanti’s 70 residents, visitors are conducted through the community by tour guides who live on site. Our local library system offers vouchers for a free guided tour, which we have happily taken advantage of. Our guide leads us under a domed structure, where we view the dirt-filled bins for casting ceramic bells and pots.

Unlike bronze bells, artists create these without hot, dangerous materials. My toddler listens intently to the description of how bells are made, then digs his little hands into the dirt and makes a circular depression—the first step for casting the ceramics. He proudly announces that he, too, has made a bell, and runs off to find the next interesting thing.

As we move on to see the stargazing amphitheater, I kick myself for deciding against a silt-casting workshop during our visit. I would love to cast a bell in the dirt, then sit cross-legged under this brightly-painted dome and cover it with Soleri-inspired designs!

“Maybe we could live here for a summer,” I whisper to my husband. He laughs, unaware that I’m completely serious. Residents can stay anywhere from weeks to years, and to me, a couple of months this wilderness retreat seems like the perfect way to detox from the pressures of life.

The Vision of Arcosanti

Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti vision was birthed at a difficult time in U.S. history. Violence and dissention both at home and abroad, increasing pollution, and consumerism culture struck deep at the souls of many Americans. It’s little wonder that so many people dared to leave behind the familiar to become part of a project like Arcosanti. Soleri hoped to influence urban design for the better—to create a workable prototype that would encourage eco-friendly, community-driven cities.

Has Arcosanti achieved that vision? Many Arizonans would say that Arcosanti has faded nearly into oblivion; just another quirky little Southwestern roadside stop. However, I would beg to differ. Despite the emergence of the digital age, Arcosanti has survived.

In fact, in many ways, it operates just as intended: a place for residents and visitors alike to escape the pressures of life outside, and to see that many of those pressures are simply stresses we place on ourselves. It gives us the chance to revel in meaningful art, and embrace the truth that beauty and community are core human needs.

To keep this in mind every day, I purchase a small ceramic wind bell with mountains etched into the surface—the same mountains visible on the horizon line of the Arizona high desert. When I get home, I hang it in my kitchen. The bell tinkles softly as I hook it above the jumble of plants on my windowsill. It’s a reminder of what truly matters in life, and that it won’t be too long before I once again travel to Arcosanti and fall asleep in a guesthouse under starlit wilderness skies.

Sources:

“About Arcosanti.” Arcosanti. 2020. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.arcosanti.org/about/

“History of Arcosanti.” Arcosanti. 2020. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.arcosanti.org/history/

Book Your Stay Now Near Arcosanti, Arizona

Use the interactive map below to search, compare and book hotels & rentals at the best prices that are sourced from a variety of platforms including Booking.com, Hotels.com, Expedia, Vrbo, and more. You can move the map to search for accommodations in other areas and also use the filter to find points of interest!

Join the community!

Join our community to receive special updates (we keep your private info locked.)